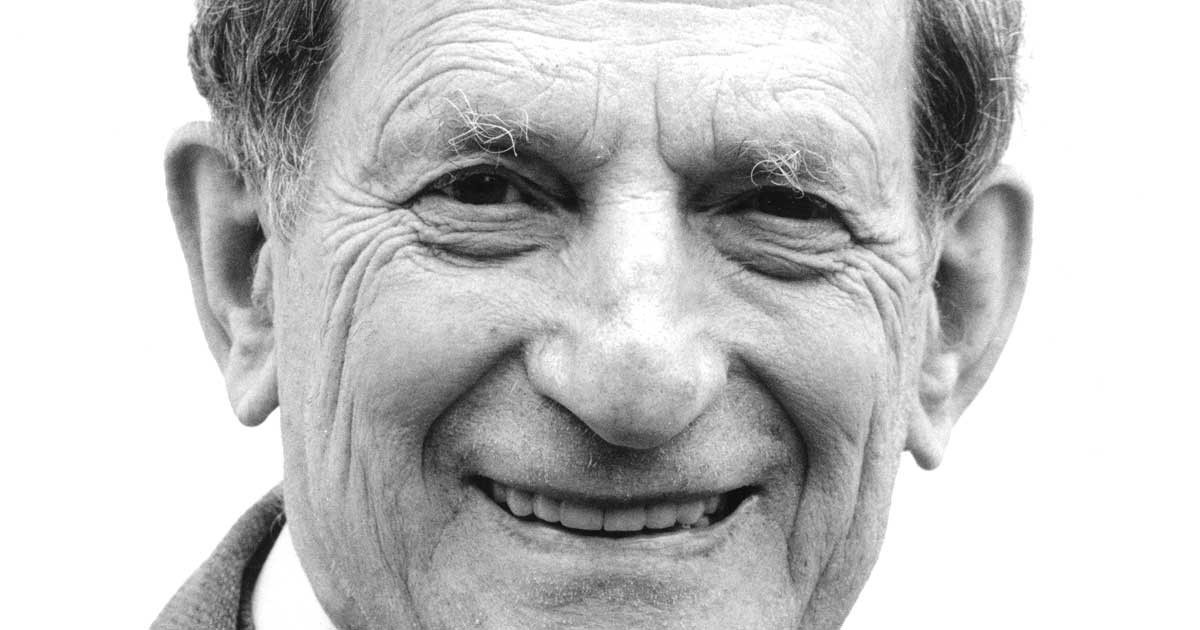

Humberto’s introduction to “On Dialogue” by David Bohm

This text from physicist and philosopher David Böhm is a gift with an incentive. It could be that this book changes you; therefore, it is a real game-changer.

David Böhm gives us hints that help us to give meaning to current contradictions between social crisis and technological utopias plus everything surrounding that, and he creates an appetite for the philosophical quest for the hidden assumption.

Although it might seem complicated, much of the knowledge in this book is directly applicable to your self. Bohm’s insights, in many ways, unmask the image we hold of ourselves.

The book undermines all certainties in our mainstream culture. It overturns the ‘normal’ way we think of ourselves and how we, with those ideas in mind, perceive the world. Smartness, abstract thinking, discussion, science, ‘peace and love’ – all exposed as more of the same. We need radical change to free ourselves from the hyper-atomic I culture, in which the human being is a stand-alone, locked up in his mind, that is perceived too often as one’s identity or even space where one can be free. It is all about the reversal of values.

Condition of the world

When Böhm wrote this text – late last century – there was not yet such explosive growth. The I phone was nonexisting! It seems that this is the perfect time to use this book.

In addition to the positive developments in cultural and social development in our completely industrialized world, many symptoms of disintegration become visible. In the observable and non-observable world, issues are affecting both society and ourselves. On the one hand, it concerns issues such as climate crisis, nuclear threats, pollution, refugee flows, and political instability, and on the other hand, phenomena such as depression, burn-outs, smartphone, and drug addiction or simply loneliness.

A tsunami is moving through our society, which we have not ‘seen’ coming, just as with the natural phenomenon. (1) A tsunami caused by exponential technological development. We could not see it coming, because until now we have always been in control of technological development. Our human mind thinks linearly. Technological progress, on the other hand, does not follow that linear line but proceeds according to a curve that we call exponential. It goes up steeply. At first, there was nothing wrong; we denied the calling of the crazy person, who warned us about the robots, artificial intelligence (AI), hyper-control, big data, and whatnot. But suddenly the curve has become visible: After a misleading period of rest, the tsunami comes up and cuts the straight line. That intersection where the linear and the steep curve cross is called the singular point, the point where we are now: It has become impossible for us to imagine what will happen tomorrow.

The necessity of new concepts

It seems that everything we have build – in hundreds of years – is no longer functioning adequately. From our thinking, acting, and feeling; to rituals, customs, and laws. But also our theories and philosophies about ourselves and the world. And this might be putting a brake on things when it comes to creating a new narrative. In short, we need totally new concepts and perhaps a complete reset of our thinking system. Maybe, an entirely new image of ourselves and our thinking.

The extraordinary thing about Böhm is that he can connect the inner and outer world in a profound analysis that makes a ‘conscious joint action’ possible.

Errors in our thinking system

In modern times, there are significant derailments, particularly in the following areas: The way we think and the way we think about our thinking; the way we think about feeling. The model we use for the ‘I’ or the ‘self;’ the way we discuss and debate; how we glorify abstract knowledge; the way we observe or perceive; how we divide everything into boxes and silos (education, government, companies, and ourselves). How we are obsessed with facts, we defend them as objective truth, and how we want to solve all problems in a result-oriented, rational way. We do not realize that the world of buildings, roads, schools, businesses, barracks, and houses is a consequence of our thinking: It is a design produced by our thinking. (2) But, vice versa, the physical world also determines the way we think.

The most crucial drama is that we do not think; instead, we repeat thoughts (thought is the past tense of thinking); so, we always spin in the same circles.

This problem occurs because our prefrontal neocortex, in which our reflective thinking situates, directly connects to the evolutionarily oldest parts of the brain – such as the amygdala – in the brain stem. In this reptile part of the brain, survival instincts, flight or combat reflexes, and emotions are the main drivers. We can’t just shake off our reptile brain.

Thinking is embodied in many neural circuits, which consist of nerves connected by synapses. When a particular such a circuit repeats a thought, it releases a shot of dopamine or serotonin, which will induce a pleasant feeling (3). Through this explanation, you can understand that the repetition of the thought, asylum seekers are criminals, makes an ever stronger circuit will secrete more and more dopamine. Therefore we say: “When you fire, you wire.”

Our thoughts are, therefore, not purely mental; they are embodied in a network of neurons partially regulated by hormones and endorphins. In short, our thinking is a physical process. The misleading thing is that these thoughts work like viruses; they are self-induced. The viruses yell ‘do me,’ and when you do so, they give you the impression that you are thinking. Here emerges the first fallacy in our thinking system (4).

The described mechanism is even stronger with hidden presuppositions or supposedly necessary thoughts, which often have a collective nature.

When someone says, “I always assume that …” then that pinpoints is an addictive necessity. Colleagues in that situation already know what person X or Y is going to say about the topic at stake; never the less the person itself thinks that he or she is thinking.

The necessities such as “Everyone does everything for their own sake” can be so strong that our neuro-endorphin system responds to threats of it with a defensive reflex.

These assumptions often installed by education, the school, church, – and nowadays, more and more media – and so-called social media. But, there are also presuppositions present in the buildings and other things in our environment. Böhm argues that we avoid any indication that these presuppositions or our necessities might be wrong a priori.

Thinking is not pent-up in our head, thinking designs the outside world and the outside world unconsciously directs the thinking process.

Much of what is now entering our consciousness through social media is, therefore, explosive viral material that shakes our thinking and feeling thoroughly. The brains behind these platforms are finally beginning to admit that they are seriously manipulating the minds of users: we can speak of the ‘hacking of the mind.’ The model of Böhm explains why platforms like Facebook and Instagram have so much influence: the physical world and our inner experience are interconnected, and our thinking and feeling are susceptible to dopamine addiction. (5)

Your experiences are an essential source of presuppositions. Many assumptions arose painfully, often in early childhood, when you were extremely vulnerable. A mother told me that on the presentation of her daughter’s master’s degree in English, her daughter came to realize that her entire life, from the age of eight, was dominated by the premise that she was stupid. Her primary school teacher had told her: “you are a lantern without a light.” All this time, she had not had self-confidence, and her actions were aiming at hiding her stupidity.

Many assumptions are hidden. It is too painful to realize they are there, at work. But, in the meantime, they operating in our thinking. There is often a paradox, says Bohm. He tells the story of a man who is susceptible to flattery. The man is conscious of his behavior and wants to change it. The assumption on which this behavior is based, however, arose from a very humiliating, painful experience in his childhood. Thought tries to avoid that pain at whatever cost, and at the same time, flattery causes a lot of dopamine releases. The pleasant feeling is suggesting that the man feels well. Therefore he is unable to come to the pain that causes his unwanted or incoherent relationship with the world. Bohm argues that feelings and thoughts arise in the same system in the same way. Negative assumptions like “I am stupid” or “I have no self-confidence” can be just as addictive as positive thoughts! Our neuro system doesn’t make a distinction; it is only an electrical current.

A second fallacy that Bohm points out is that thinking hides its effects: it shows the world as if it is a fact. It seems like a passive medium that communicates what we perceive in the physical world. But, in fact, it creates the world; and then it tells us: I didn’t do this. The thinking that observes problems in the world ignores the fact that precisely that thinking causes those problems. The world is a consequence of our thinking. The existence of nations is a consequence of the collective necessity that we attribute to that concept. We can keep on debating, but we can also carefully look at the implications of our thinking and its origins.

We create abstractions with our thinking, and we accept these abstractions as truth. The map of Barcelona is an abstraction, quite literally a: subtraction of the real city. Suppose we accept this map as the truth – that would be crazy. Precisely that is what we do with our abstractions and models that our mind projects. Nationality and nations are a strong example of it. The philosopher John Dewey called this systematical error “the intellectual fallacy.” The more abstract something is, the more the “truth” we find in it. That is why science has become today’s religion. (6)

A third fallacy, related to the previous one, is our inability to listen. We are so addicted to repeating our own thoughts and ‘felts’ (past tense of feeling) that we only take in what fits those thoughts and ‘felt’.

People who claim to listen can often not reproduce what someone has said.

Sometimes we don’t listen because we unconsciously defend our assumptions connected with vulnerabilities or fears, we are on our guard, as a defensive reflex.

Listening is an art that can create entirely new kinds of interactions. Attention – a crucial concept for Bohm – is a catalyzer in this process.

The fourth fallacy is the idea of the isolated self, (the stand-alone) the I. This I reasons as follows: My thoughts and feelings, must be caused by me as a thinker, so all my thoughts and felts must logically be mine. This line of reasoning completely denies the external and collective nature of our character. The idea of the “I-think” is one of the persistent necessities in our culture. The concept manifests itself in the way in which we are always addressing our unique, “free” I. (7) According to Bohm, this leads to discussions, which essentially boils down to handing out punches (the words ‘discussion’ and ‘percussion’ have the same root). In debates, we lock ourselves in a misleading self-image. Heart rate, blood pressure, adrenaline – everything is on in a debate modus, the animalistic part of the brain dominates.

What to do?

The book gives a clear response to the fallacies in our thinking system, outlined by Bohm.

We must realize that our thinking system as we experience it today is strongly related to our writing, which we have only developed for the past three thousand years. Before that, only the oral method was practiced in dialogue. This always happened in collective contexts. Tribal communities mainly knew the ritual of communal attention. The written word enables isolated reflection (a development that is further enhanced by the internet and mail). The dialogue separated from thinking.

In this book, Bohm shows that we always have to enter into a dialogue to understand our thinking.

You can enter into a dialogue with yourself by observing your thoughts and feelings as if they are impulses that come from outside. You can “suspend” an emerging (negative) thought, by asking yourself: Do I want to think this? Bohm calls this “self-perception” proprioception. We are used to looking at our body regularly (eg, in the mirror every morning); you should do this with your thinking and feeling as well. Proprioception allows you to penetrate deeper into your own assumptions. Your mind will enter its creative mode this way.

In groups, we can conduct a dialogue that transcends discussions and debates. The art of listening is central to dialogue. In our society, moderation is necessary to lead people away from their I-orientation and efficiency-oriented attitude to listening. When different positions are exposed, it is not primarily about discussing and exchanging arguments, but mainly about deepening: the presuppositions of both positions. In joint concentrated attention, the whole group looks at the underlying thoughts. The joint proprioception that arises creates a sense of community.

In the dialogue group, the collective attention creates a “participatory awareness” in which and in which all participate. This participatory consciousness is much greater than the abstract thinking; it can produce much more profound insights starting from tacit assumptions.

On your own, this will not work because most assumptions are collective. In a mini culture of the group, we can expose the disturbing presuppositions and jointly produce new meanings.

Because you practice the art of listening, you start to absorb the thoughts of others, and you become detached from your system of thought.

The participatory consciousness helps us to solve particular technical issues in our ordinary thinking. Besides, the participatory consciousness is a fantastic response to the described fallacies of our time.

Thinking from this participatory consciousness, we capable of designing entirely new realities. Participatory awareness is a natural activity and can heal fragmentations arising from ‘stand-alone’ thinking. It creates the possibility to deal with the exponential technological growth with entirely new concepts because our intelligence – which occurs in our shared participation consciousness – is no longer tied to the old ballast. The collective attention does not coincide with rational thinking but is necessarily physical, meaning that artificial intelligence (AI) can at most support us in this.

The Challenge

Bohm’s bundle on dialogue is a gift and an incentive. As for the latter, the challenge is to create tribal contexts within which we can give new meaning to our existence, meaning that does justice to people’s authentic desires. The meaning is already in the joint, attentive concentration on our tacit ground.

The genius is that you can start with this tomorrow: create a new self within a community.

But that doesn’t happen overnight. It is advisable to cherish this book for a while, to appreciate the meaning of this book thoroughly, you have to let it penetrate quietly.

The challenge is to critically re-evaluate all products produced by our ‘stand-alone’ thinking and feeling and, if necessary, to replace them with creations of the participating consciousness. This applies to individuals, to companies, but also major political conflicts.

Humberto Schwab, Sant Climent Sescebes, Spanje

- ‘A Tsunami of Change’ – Yuri van Geest op Our Future Health 2016

- In Socratic Design practice, individuals and companies learn to create new realities with new facts based on this insight.

- Thought as a System (1992, Routledge, New York) also features several seminars that highlight this effect in particular.

- A system error in physics is an error in the measuring instrument; it will often be unnoticed.

- See also: Robert Lustig, The Hacking of the American Mind, Penguin Random House, New York, 2017.

- Logical positivism has gained mass.

- See also Mark Johnson, TheMeaning of the Body: Aesthetics of Human Understanding. University of Chicago Press, 2008, p. 105.