Design your habits

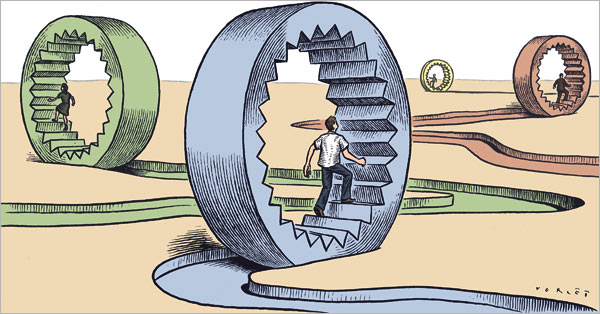

a drawing by Christophe Vorlet

We all have good intentions, especially after the holidays; we want to talk more with the family, improve your relationship, stop smoking, quit drinking, do more sport or consume less meat and watch fewer screens. Also on the level of our professional life, we have good intentions. We want to plan better, have fewer meetings, do what we agree on, communicate better with our colleagues, be more helpful to clients and be more proactive or even change jobs, tell the truth to your boss and colleagues, start a new life! How disappointed we are when after two weeks we realize we are acting and thinking the same as before the holidays.

If you assume you can stop smoking just by deciding so, that you can stop being addicted to your screen just by decision or that you can improve your relationship only by expressing your intentions, you are assuming that human beings are rational agents.

We expect that we can take rational decisions which – in a sort of command control relation – will be obeyed by the body or by whatever emotional system. We even think that we can change the behavior of people in groups by giving rationalized rules. We organize a meeting, discuss the problem, and look for a rational solution. Or worse as leaders we give out orders that people should change their behavior and then go home, expecting that you have completed the job.

That we regard ourselves as rational agents is based on several implications:

- We think that our identity rests in our thoughts and rational deliberations. It means that we continually live under the spell of the demand for consistency. We create a logical self-image. If I believe A, then the next step must be B. I have to radiate a coherent and consistent `personality.

- We think that we can solve problems by logical thinking, we then take in mostly intellectual elements of any issue at stake.

- All problems will be first abstracted into a rational language to solve it, emotions, intuitions or other vague notions we eliminate.

In short, we conceive any problem as a logical abstract theme, that has to be solved with a logical precision of cause-effect reasoning.

Although good thinking is an essential value in our civilization, we are not only rational creatures. We are more embodied than we usually want to acknowledge.

Opposite approaches have always challenged the dominant rationalistic, dualistic philosophy: it could be a monistic, mystic, phenomenological, pragmatic or spiritual angle of thinking.

The dominant folk philosophy (also to refer as rationalistic, empirical, mechanical awareness), assumes a completely independent, autonomous actor with no dependency of the environment. The connection between the outer and inner world was guaranteed by an almost mystical parallelism. Anyway, the perfect representation of the outer world is always projected in our minds.

But, we depend strongly on the inter-actions our system has with the environment. To understand this we need to look at animals and take into account our resemblance to them.

When animals mate they are working on specific cues, some fish will (try to) mate with round objects because that is what they are usually are attracted to by their potential partners, that is their cue. They do not choose their acts; they perform a habit.

There are systems in our neurological system that favor the repetition of behavior. In our evolutionary past, rehearsal was a key for survival. When a tiger approaches us, a swift reaction is life-saving and a moment of reflection could be disastrous. So, our neuro system rewards the rehearsing of that sort of neurocircuits, with a sweet dopamine release.

Animals have a fixed reaction system that is life-saving in the jungle but could be the cause of strong blockades for humans in modern society.

We are partly like our animal predecessors, we cannot get rid of our dopamine-based rehearsal system, so we are prone to behavior conditioning. We will develop very easy and fast fixed habits, habits that are hard or impossible to change, and easy to wire.

We can understand ourselves better if we consider ourselves more as habit animals. You cannot tell a dog not to sniff at the guests. You have to train him.

We have to consider our whole dopamine-serotonin system as the base for all interactions with the outside world. We are NOT rational agents that have command over our bodies; we cannot decide who we are, without taking into account the interactions we have with the environment.

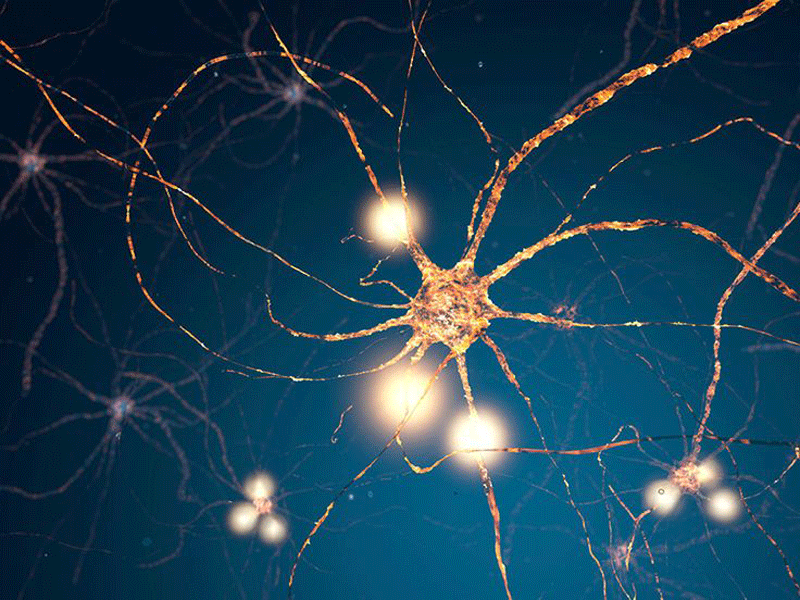

Instead of saying Cogito Ergo Sum (I think therefore I am), we better say; Synapso Ergo Sum. The synapse is the place in our neuro center where all the stimuli pass via chemical compounds. It is the connection between two neurons (axon and a dendrite), we have 12 billions of them. Any thought, feeling or action is always related to an electric current that wires in a neuron circuit. This neuron circuit will increase in strength, every time you have the same current running through the same circuit. It will harden the circuit with every repetitive thought, feeling or action.

“When you fire you wire”: when repeating that thought you will engrave it deeper in the brain tissue.

The essential point here is that the closing of the circuit provokes the release of endorphins (dopamine or serotonin). You feel nice when you repeat the same. Dopamine is related to circuits of our brain stem (the oldest part of our brain), serotonin release is related to processes in the neocortex (the youngest part of the brain).

We can say that all our thoughts, feelings and actions are stimulated, feed or incited by dopamine or serotonin releases. This makes clear why we are so attached to the same behavior, or why we have a fixed character and why we keep on saying the same things over and over again.

Above all, it explains why we humans are so perseverent in sticking to our habits. Some even refer to their habits as an essential part of their character.

The origin of the meaning of the word “habit” is very remarkable, it was a denotation for clothing (of a monk), it stems from habere, which means “to have, hold, possess; wear; find oneself, be situated; consider, think, reason, have in mind; manage, keep”. The Latin word habitus refers to an internal or external state of being, alike!

The rich meaning of habitus is showing us the full range of this concept: it can be physical, mental, moral or even partly outside us. Here we can return to the Cogito Ergo Sum approach (I think therefore I am), which is not capable to understand the complexity of a habit. A habit is an inter-action between an internal state of our synaptic system (in which thoughts, feelings, and sensations mingle) with the external world of impressions and (re-) actions (that also travel through the synaptic system). It is a closed circuit between your inner elements and the outer elements.

When you see the Marlboro logo, your “Synaptic Self” is already ready to smoke. When you see the red wine bottle, the system has awakened all the taste related neurons and the happy thoughts we have about getting “relaxed.” But, also, small molecules in the external world (pet allergens) can produce the body to a forceful reaction.

Your system is continuously alert on cues that wait to be followed up. It can be the lounge chair, the coffee machine, the laptop, your Facebook/Tinder or the sugar in the products you eat.

The habit is strongly engraved in the Synaptic self, so, if somebody grabs your fresh newspaper, or takes your preferred parking lot, sits on your office desk or hides your phone, you can get pretty nasty.

We also create habits in the way we talk (or not talk) to our closest friends and family, to our colleagues, to our students and clients. We create habits in how we move, behave, act and so on. These habits are not always visible, because: also collective habits are rooted within our Synaptic Self. When you start a new job, your chief will explain procedures and rules, but very soon after you start, you will encounter an entirely different group of colleagues bound by specific habits. These habits are mostly not connected with the policy of the company. Colleagues will introduce ways to avoid controls, to deal with that boss, to escape the rules, or to get easy benefits and so on and so on.

Your habits are partly inside and partly outside you. They also do not always obey your values and goals, for some people they even fully ignore the set-out values and goals.

We can have habits work entirely against our purposes and intentions.

We can only understand this complex phenomenon when we start from an entirely different philosophical assumption. Man is NOT a rational creature, but an embodied mind, organized by the inter-action between the inner and the outer world. We are more about our experiences then we are about our thoughts. We are what we act, more than what we think. We have strong ties to our external surroundings. Saying that you are in charge of all your thoughts, acts, and feelings, is like a drilled circus elephant who – while performing all sort of tricks – believes that he is acting on his free will.

All our intentions will evaporate against the force of habits. To make things worse, most habits are unconscious, they are ignited on us by external forces we often do not observe. If we look at it like this, we can see that we are partly victims of habits, we do not see the compelling force they have on us. So, we drastically need another model of our self or create another self-image to organize ourselves better.

Let’s go to Dewey.

Experience – according to the philosopher of American pragmatism John Dewey – is the unification of different inward processes and the process of acting by us on the outward world, resulting in an esthetic creation that gives us a deep feeling of contentment.

To have a perfect experience (“having an experience”) you need a good preparation (therefore you rehearse the coming experience in your mind), what we normally call thinking is preparing the (inter)-action. A good preparation means that you act according to your previous actions, directed step by step towards a purpose and that it is part of an ongoing learning process. It is as well an esthetical as an ethical event.

A good inter-action is a creative process that resembles the making of a piece of art: it is far more challenging to make a good painting or a good sculpture than solving the Schrodinger equitation in quantum physics. Our thinking processes are not the crown on our being; They are a preparation to the highest form of our being: the esthetic experience.

So, when we believe in our thoughts as the highest levels of being, we make two fallacies. First, we ignore that we are always embedded bodily and mentally in the world, secondly, we ignore that our habits of thoughts and actions, make us entirely dependent on cues that trigger our dopamine/serotonin reactions. Instead of being creative, we are mostly performing addictive reproductive acts.

If you realize that human beings have a deep inclination to mime the other person; that we are full of mirror neurons and therefore automatically copy the behavior and feelings and thoughts of other persons, you can realize that we are trapped in a spiderweb of common habits, that bind us to each other and our environment in an eternal repetition, like Nietzsche’s Wiederkehr.

If Dewey is right, then we mostly do not have experiences, we have addictive habits that keep us in the box, because of their dopamine-serotonin system. Because this self-deception is so satisfying, it is hard to beat; we enjoy staying in the box too much because of the continues drug deliverance in our system. It appears that especially dopamine provokes this comfort level addiction.

After years of scientific investigation, Robert Lustig (see book cover) cannot avoid the thesis that our bodies and minds are hacked, thanks to the dopamine circuits related to sugar. We are unaware of the exponential increase in sugar consumption, and hence to the rise of dopamine dependency. Our eating and drinking habits are one of the strongest to change, but also most easy to install in us from the outside.

A simple example is a way supermarkets place vegetables and fruits and the beginning of the routing and chips and sweet in the end. The longing habit for sugar is not hindered by a moralizing superego, because that is already satisfied by the vegetable intake in the beginning.

How can we get out of the circle of comfort level addictive circuits?

We are always longing for real experiences, to escape from routine we dance in the weekend, jump from mountains, hike in wild nature, go to exotic places, engage in strange experiences or deep dive into mystical revelations, with or without drugs.

Is all repetition bad?

Well, the truth is we cannot live without habits, we cannot live without some structured solid neuron circuits. If we were always completely open, our neurons would be a jungle (the neurological jungle of Michel Onfray)!

Also, we want communities to function organically; we want to raise kids, educate adolescents, create a stable society of clear values.

Your values are one of the most essential elements of your being, and fixed neuron systems should maintain them.

To know your habits, you need to observe yourself and your community carefully. You can do this by investigating all sort of automatic cycles in your behavior. Find out what the trigger is for specific behavior and what the satisfaction is. Above all ask your self “why am I doing what I do?” Or “why do we work the way we work?” Or why we as Dutch, French, Germans have these habits? What are they implicating, what sort of assumptions?

If you have the addictive habit of swiping tinder profiles, ask yourself if you want to be such a person. The value question is key, but we cannot kill an unwanted habit easily, de engravement is very deep.

We as French have the habit of organizing ourselves hierarchical, we Dutch always keep focusing on utility, we Germans like strict rulings and the Spanish do want the quality of the moment. You can generalize about national cultures because these cultures have programmed the habits of the masses.

Again we are dependent on our environment; it determines our inner and outer selves. If we want to change we have to change our habits or better said we have to replace old habits with new ones! The habit of celebrating Queensday in the Netherlands as an ongoing party was already a new habit after three years. In general, we say that a new tradition is born after two years of repetition.

For a person, an organization or a nation, in order to create good habits I can mention two conditions.

– They have to be in line with your values and purpose(s) in life.

– They have to work in the serotonin more than in the dopamine range.

Values and purpose should be translated into the way we do, feel and think. Even the toilet of a restaurant reflects some value habits. The way people in villages greet each other is a design of good habits. You can introduce that for example in cities; as they successfully did in a neighborhood in Rotterdam. When neighbors treat each other competitive or even egoistic and antisocial, everybody will become like that.

You become how you behave. So, we are egocentric because we based our design on the assumption of egoism and structured it in the design. If we installed new habits based on the assumption that men are social, empathic creatures, everybody would be empathic and social. The power of Dewey’s model is exactly that; we are our (inter)actions, so if your actions are good, you are good.

How can we get rid of the low-level habits of sugar, swiping, alcohol, drugs, and porn? The so-called dopamine pleasures. Robert Lustig stresses the difference between pleasure and contentment.

Simple pleasure is related to the dopamine receptors in the brain stem, the oldest part of the brain. In this part, strong emotions are triggered and thus also strong addictions. These – old brain – dopamine pleasures have in common that they always demand an outside object and that they always want more of the same.

Nevertheless, we also want variety in our lives; we want to grow, we want to experience or to put in bluntly: we want to live.

The challenge is to find a good balance between addictive, repetitive circuits and real experiences that are not repetitions.

We should surround us with things and people that trigger “real interaction,” “real experiences.” The serotonin habit is something that looks like the experience of Dewey.

Serotonin receptors (situated in the neocortex) are responding with experiences that demand a high level of complexity, from body and mind. Making a drawing, solving problems, making furniture, playing an instrument, cooking, design new practices, these are all activities that create contentment and can always be generating new content.

In the balance between fixed neuron circuits and the more creative -hic et nun – experiences, we should always look for fixed habits that are focused on experiments. We have the splendid contradiction that we use our low-level addictive circuits to maintain a permanent openness to high-level experiences and interactions.

We should design our cultural environment on all levels as exciting, experience-oriented events. We can do that for our private life, for our business and school, and for our public life.

If you have the habit in the company that the team makes every important decision in a Socratic (Design) dialogue, you will have a different group with responsible members.

If you develop the habit of intensively listening to your partner and take the time to go deep in his or her story, you have e new relation. Install this habit in your life and repeat it so it can become a dopamine triggered response.

To find our best habits we need to analysis ourselves and our cultures by exercising collective attention, the key habit of Socratic Design.